Expanding the Canon and Conversation: The Paintings of Amy Sherald

Video Still of Amy Sherald in her studio. Image Credit: Hauser & Wirth Website

Why are Black faces, bodies and experiences largely absent from artworks displayed in museums and galleries? (Except perhaps for the occasional show or artwork that checks the diversity box.) Why do we seldom — if at all — learn about Black artists when studying Art History? Why was I (are we!) only taught one side of history that excludes the stories of Women and People of Color (except for a “token” few)?

Last fall — a lifetime ago — I was introduced to Amy Sherald’s profound portraits of “everyday people.” Her practice focuses on capturing the inner-self of her sitters rather than their exterior or public Black-selves, which is highly politicized in the eyes of “society.” There’s a serene gentleness to every painting, as each individual is depicted beautifully poised. After rereading the review I wrote of her exhibition, I kept thinking about her paintings in light of the current Black Lives Matter movement, and the goals it’s activists are fighting to achieve. When you boil it all down, their request is simply equality. They are asking to be treated with dignity and fairness, to have a true equal shot, equal representation at the table, and, for once, to be viewed and acknowledged as “everyday people” in America by all Americans.

I hope you agree after reading my review below that Sherald’s work is so very critical to the current conversations about race and equality— especially as it pertains to the contemporary art world and art history. We, as allies and activists, have a lot of work to do. Looking forward to the discussion!

Installation Photo of “Amy Sherald The Heart of the Matter” at Hauser & Wirth, New York, 2019.

Expanding the Canon:

an Exhibition Review of “Amy Sherald the heart of the matter...”

Hauser & Wirth — New York, NY — September - 26 October 2019

On the Saturday afternoon of closing weekend, the typically vast, echoing space of Hauser & Wirth’s second floor gallery filled with visitors. Art enthusiasts — from myriad racial backgrounds and economic status — crowded the wide spaces between Amy Sherald’s six life-size portraits and two monumental paintings of “everyday people.” The canvases were hung sparsely in the large L-shaped space, allowing small groups of people to pool around each artwork waiting for their moment to engage with each painting, thoughtfully placed at eye-level. The effect — whether by intention or chance — was an intimate conversation between the viewer and painting.

Amy Sherald, an American portrait painter who recently moved to Brooklyn from Baltimore, is best known for her arresting portrait of First Lady Michelle Obama, 2018. (Currently on view at the National Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C.) The large painting depicts a poised Mrs. Obama seated and wearing an elegant evening gown. She emits a calm, yet pensive expression as her chin rests on top of her hand and her distinctive eyes focus outward to meet the viewer’s gaze. The work expresses the gravitas of her public persona, while underscoring the qualities that made this famous sitter so approachable. Indeed Sherald said she envisioned Mrs. Obama as someone, “women can relate to — no matter what shape, size, race, or color… We see our best selves in her.” More than its content, however, the painting may be even better known for its historic nature: It was the first portrait of an African American First Lady, and the first time a female African American artist was hired for the prestigious commission.

First Lady Michelle Obama, 2018; Oil on linen; 72.1 x 60.1 inches; Collection of National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution.

Miss Everything (Unsuppressed Deliverance), 2014; Oil on canvas; 54 x 43 inches; Collection of Frances and Burton Reifler.

However, Sherald is no stranger to being a trailblazer. In 2016, she became the first woman and the first African American to win the National Portrait Gallery’s Outwin Boochever Portrait Competition for her work, Miss Everything (Unsuppressed Deliverance), 2014. The win put her in the running for the presidential portrait commissions. Since then, her career has taken-off. She received her first solo, traveling museum exhibition originating at the St. Louis Contemporary Art Museum in 2018, and this exhibition — Amy Sherald: The heart of the matter — was the artist’s first with Hauser & Wirth since the Swiss-based New York gallery began representing her earlier this year.

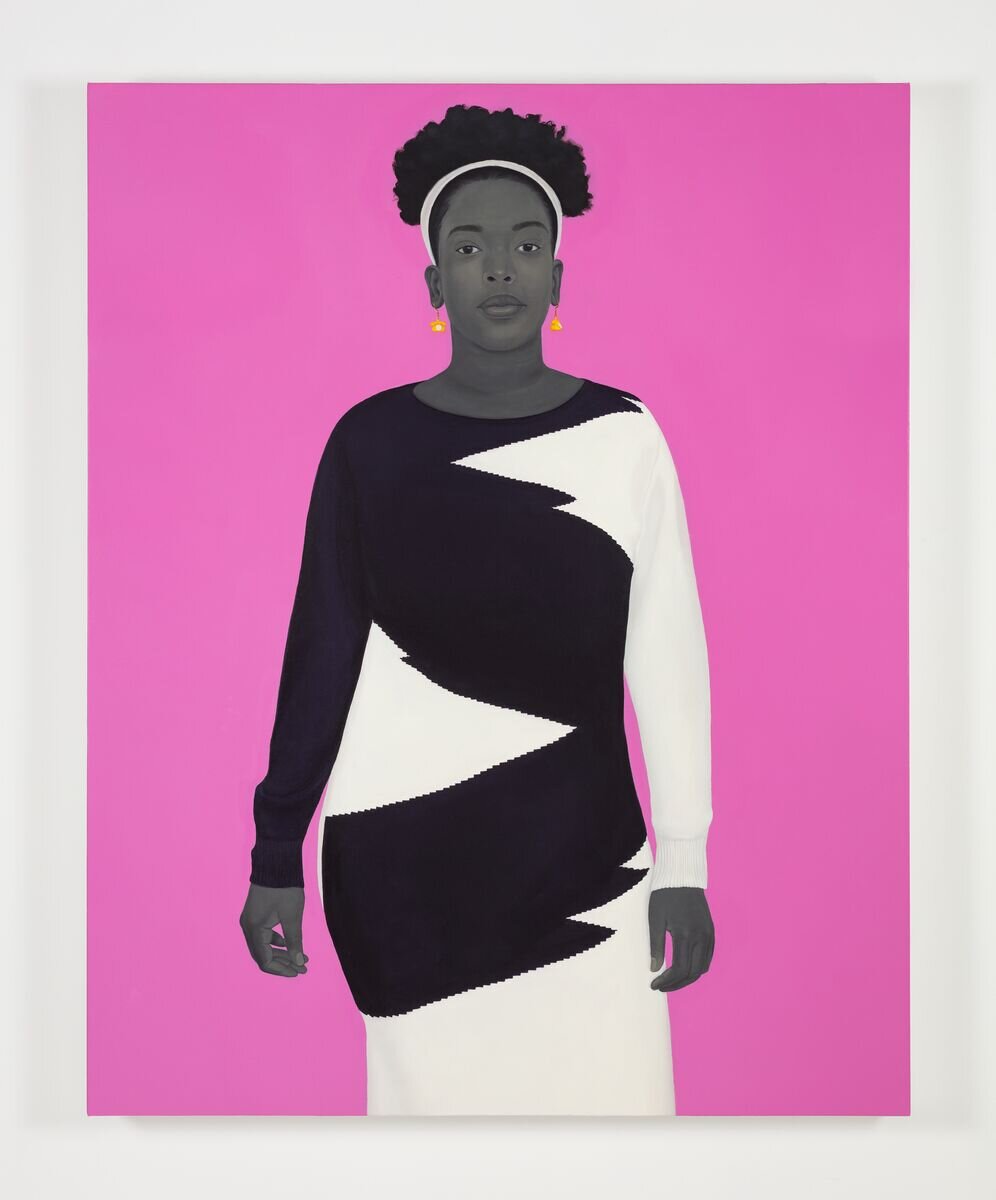

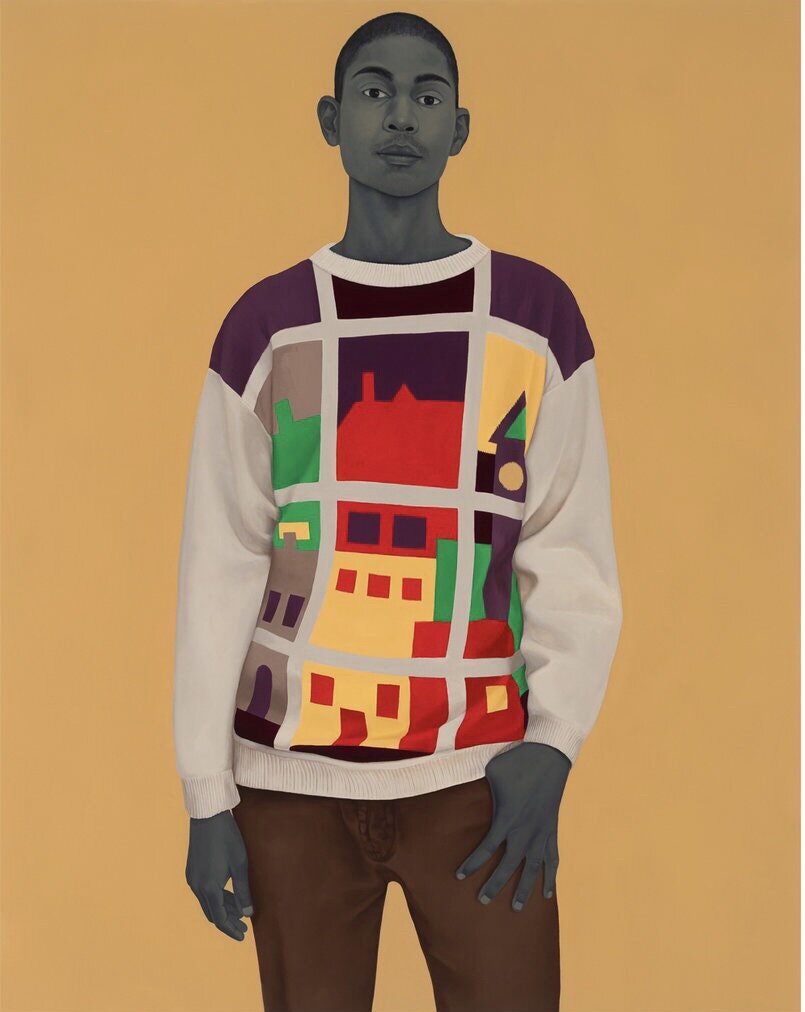

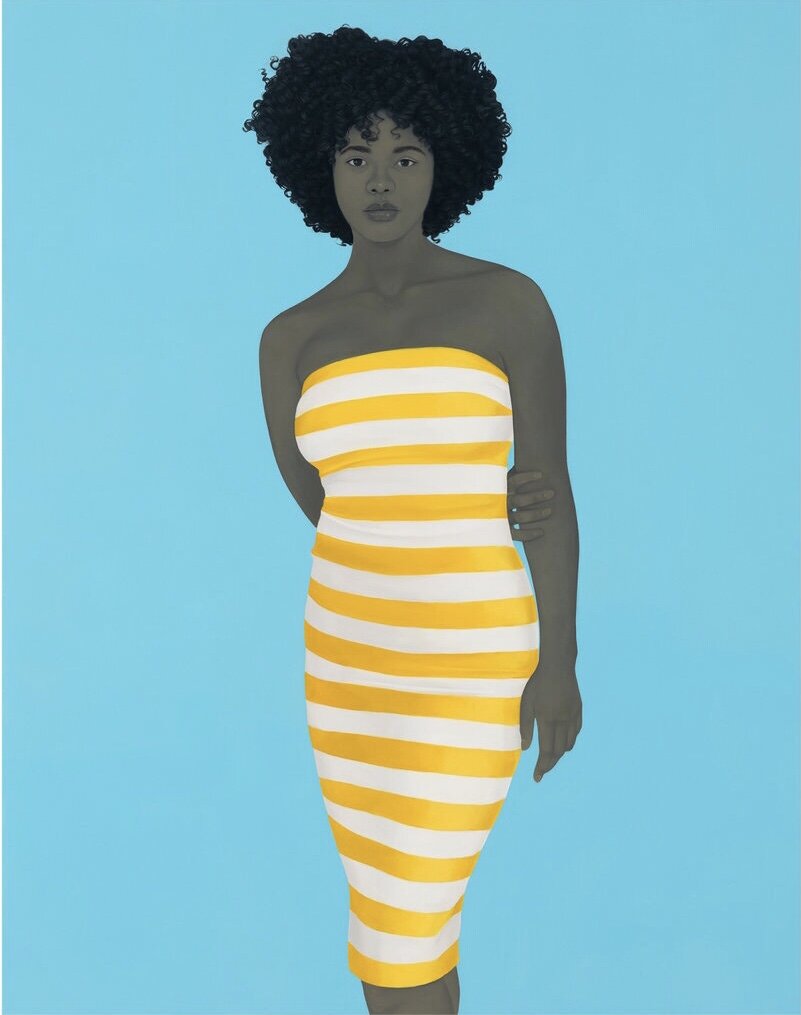

Sherald’s subject matter is straightforward. She creates portraits of African Americans who are the “everyday people” she sees in her everyday life. She recruits individuals that she encounters while riding the subway, walking in her neighborhood or meeting through a friend — like the model for Handsome, 2019. She then photographs them back in her studio, occasionally dressed in fashionable eclectic outfits she’s accumulated from eBay and second-hand stores.

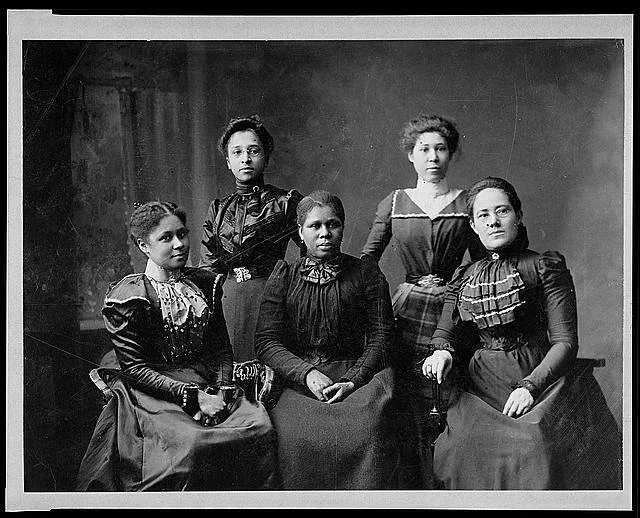

The artist is also well-known for only painting her sitter’s skin color in grisaille. This gray scale has a dual purpose for the artist. As an aesthetic choice, the muted tones allow the portrait to stand apart from the works’ brightly-colored backgrounds and clothing. Additionally, the uses of gray represent her appreciation of historic black and white photographs of African Americans, including: James Van Der Zee’s work during the Harlem Renaissance; W.E.B. Du Bois’s collection of photographs for the 1900 Paris Exposition; and also a deeply personal photograph of Sherald’s grandmother.

James VanDerZee, Studio Portrait of Young Man with Telephone, 1929, gelatin silver print, Smithsonian American Art Museum

Unknown Photographer, 5 female Negro officers of Women's League, Newport, R.I., ca. 1890s, from W.E.B. Du Bois’s collection of African American Photographs Assembled for 1900 Paris Exposition. Image Source: Library of Congress

All the three-quarter length paintings in The heart of the matter are highly individualized yet maintain the same serene facial expression. Each portrait displays its own personality that the artist meticulously crafts using fashion — clothing and hairstyles — and body language — the varying positions of each subject’s hands. The artist’s choice of bright colors attracts our eye and pulls us towards the work, but meeting the gaze of each model is what encourages us to linger.

Handsome, as the title implies, is one of the most striking works in the show. This young man dons a short-sleeved, navy button-down with pale blue polka dots paired with relaxed fitting white jeans. His demeanor is calm with his shoulders relaxed and arms loosely at his side. Like the other portraits, he engages the viewer directly. It’s as if he knows us… but from where? This instance of recognition encourages us to hover a moment longer, to reflect on that fleeting familiarity. Unlike the vibrant colors that permeate other portraits in the show, Sherald chose a muted palette— especially the plain, sand-colored background. Effectively, the work seems to rely on his beauty alone, with that familiar gaze, to engage viewers. Perhaps this is the artist’s way of showing that she’s not the least bit intimidated to experiment and detour from her comfort zone of bold color selections.

Handsome, 2019; Oil on canvas; 54 x 43 inches

If you surrendered to the air, you could ride it, 2019; Oil on canvas; 129 15/16 x 108 inches

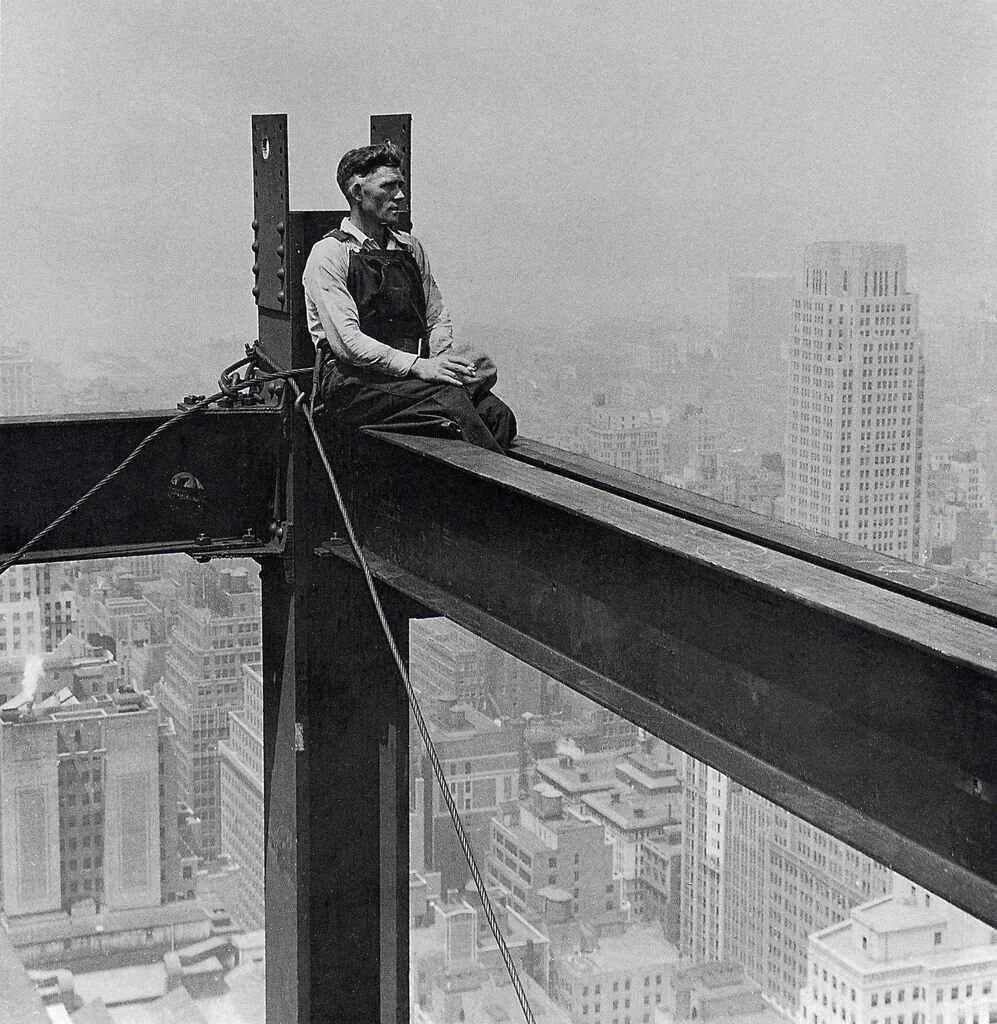

“If you surrendered to the air, you could ride it” emanated the boldest statement of the show. This seminal work was one of Sherald’s two oversized canvases— her first time working at this scale. The composition, as art critic Roberta Smith astutely identified, emulates a 1930’s photograph by Charles C. Ebbet of the now 30 Rockefeller Center as it was being erected. In Ebbet’s photograph, a white man sits in the corner of intersecting gerters. Dressed in overalls for construction with hat in hand, he appears on a work break as he stares off into the distance at the dwarfed, surrounding skyline. By contrast, Sherald’s African American sitter dresses in contemporary, fashionable clothes: a stark white turtleneck, an orange knit hat, tangerine pants with thick vertical white and gray stripes, and a matching canvas belt pulled tightly at his waist with the flap dangling over the girder.

The seafoam colored steel beams, the flatly painted cerulean sky, and his grisaille skin empower the painting with a Magical Realism that completely envelops the viewer. He stares at us with fixed eyes, his mouth slightly agape. We may imagine that he will momentarily recite the very title of the work, which coincidentally is the last line from Toni Morrison’s novel, Song of Solomon. Perhaps this was the artist’s intention — a depiction of the heights to which we could all climb, if we so choose; a whispered inspiration for any of us willing to listen.

Charles C. Ebbet, Untitled (Steelworker on the ‘in process’ RKO Building in Rockefeller Center), ca. 1932; Collection Unknown.

One of Amy Sherald’s most admirable qualities is her awareness of where she fits in the art historical canon. There’s a large gap, or more accurately an absence, in the American realist tradition of representing “everyday” African Americans. The exhibition’s press release included this fitting quote by the artist,

“I look at America’s heart - people, landscapes, and cityscapes — and I see it as an opportunity to add to an American art narrative… I paint because I am looking for versions of myself in art history and in the world.”

The artist acknowledges that most depictions of African Americans are linked to a “public black-self” that is “always attached to resistance.” Yet Sherald pushes beyond that narrative to show who African Americans are, rather than just what they’re skin color represents politically, particularly in the context of United States history. Through her paintings, she’s able to gently guide viewers to grasp the whole story. We are pulled to her work with bright colors and bold patterns, and, for non-black viewers especially, disarmed of our prejudices of race through gray skin-tones and are greeted by each sitter with that invariably visceral gaze. Yet her work challenges every viewer to dig deeper, to really “see” the interior-self, to acknowledge the individual and to — for a moment — eliminate every label and category except, perhaps, American.

Sherald’s work, is best experienced in-person. Photographs and Instagram feeds of her paintings diminish the most important elements— the human scale and personal interaction. So it is truly wonderful to hear that every painting in this ground-breaking exhibition was in negotiations to be placed in museums. With a sigh of relief, we can all look forward to experiencing these paintings in-person (even if it must be with a crowd!) with a chance to see, and be seen, by Amy Sherald’s “everyday people.”